Billions of tons of plastic are choking the ocean. She’s here to clean it up.

17.6 billion.

That’s how many pounds of plastic end up in the ocean on average each year, according to estimates published in 2015.

We know of this plastic, but one of the big unknowns is figuring out exactly how much of that debris is floating in the ocean, let alone how to clean it up.

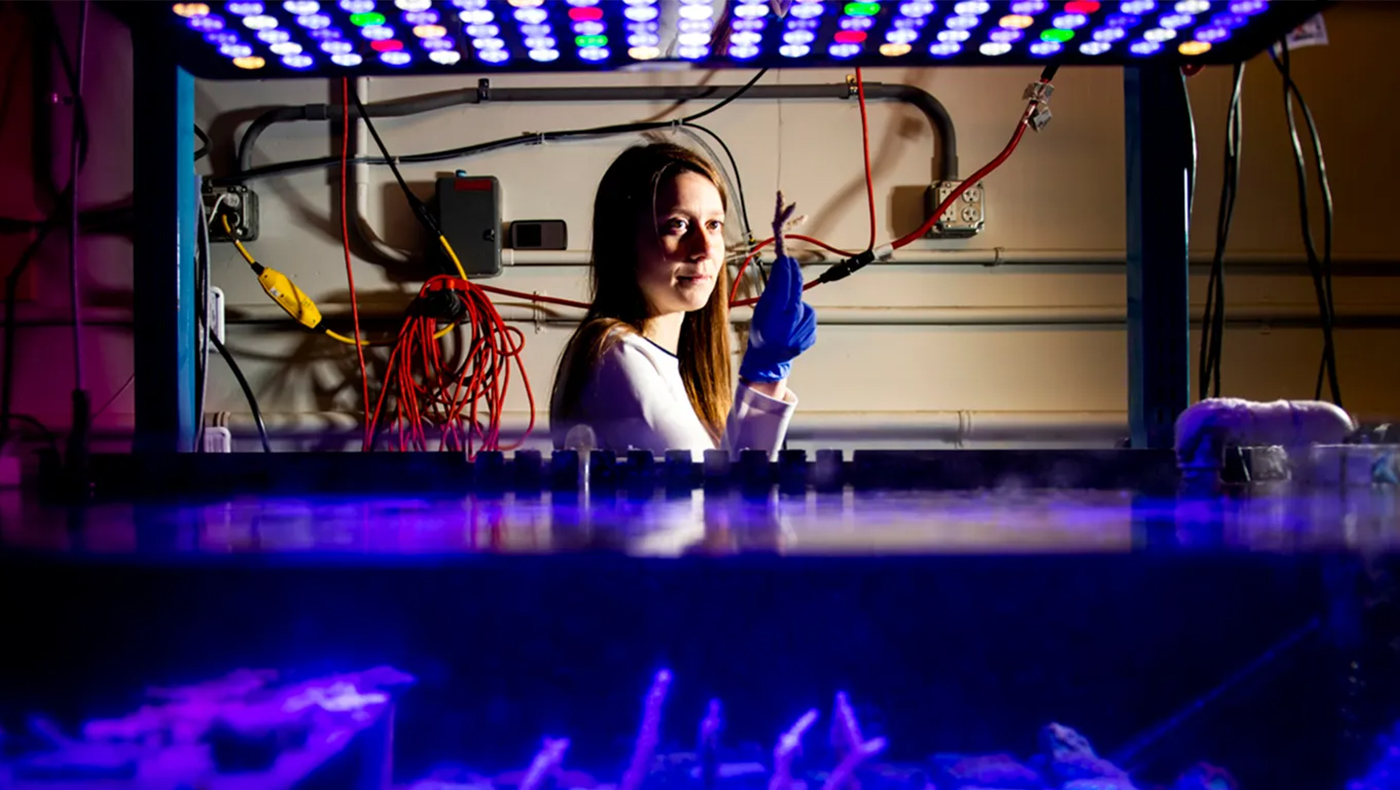

Amanda Dwyer, a graduate of Northeastern’s doctoral program in marine and environmental sciences, is on a quest to address that challenge.

“The best way to prevent this problem from becoming bigger is to decrease the amount of debris that can end up in the ocean,” Dwyer says. “Despite our best interests of trying to reuse and recycle, reducing is the first part of that mantra.”

Dwyer is moving to the Washington, D.C. area to work behind the scenes of research. Her expertise will add to the federal government’s leading office for addressing marine debris at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

At Northeastern, Dwyer has also tried to inspire the next generation of scientists through the Beach Sisters program, which helps young girls learn about marine science and involves collaborating with other nonprofit and governmental organizations to lead community service projects and afterschool programs. Working with Massachusetts State Rep. Lori Ehrlich and other state officials, they helped create an initiative to ban plastic bags.

“It was really the work of these peer leaders, these high school girls from Lynn [Massachusetts],” Dwyer says. “But that side of policy things really got me wanting to learn more about how that works at a national level.”

Dwyer wants to use what she learned from that experience to reach out to people outside her field. That, she says, might be one of the toughest challenges at the intersection of science and policy, especially for scientists who occupy a highly specialized niche.

“It can be hard to get someone to your level of passion,” Dwyer says. “It’s about making sure that you’re communicating [research] to someone who hasn’t been spending every day thinking about these problems and to someone who is actually going to be enforcing the policy but who also has so many other different issues to be concerned about.”

Read more on Northeastern Global News.

Photos by Ruby Wallau/Northeastern University

Author: Roberto Molar Candanosa