To predict our future climate, they’re digging into the mud of the past

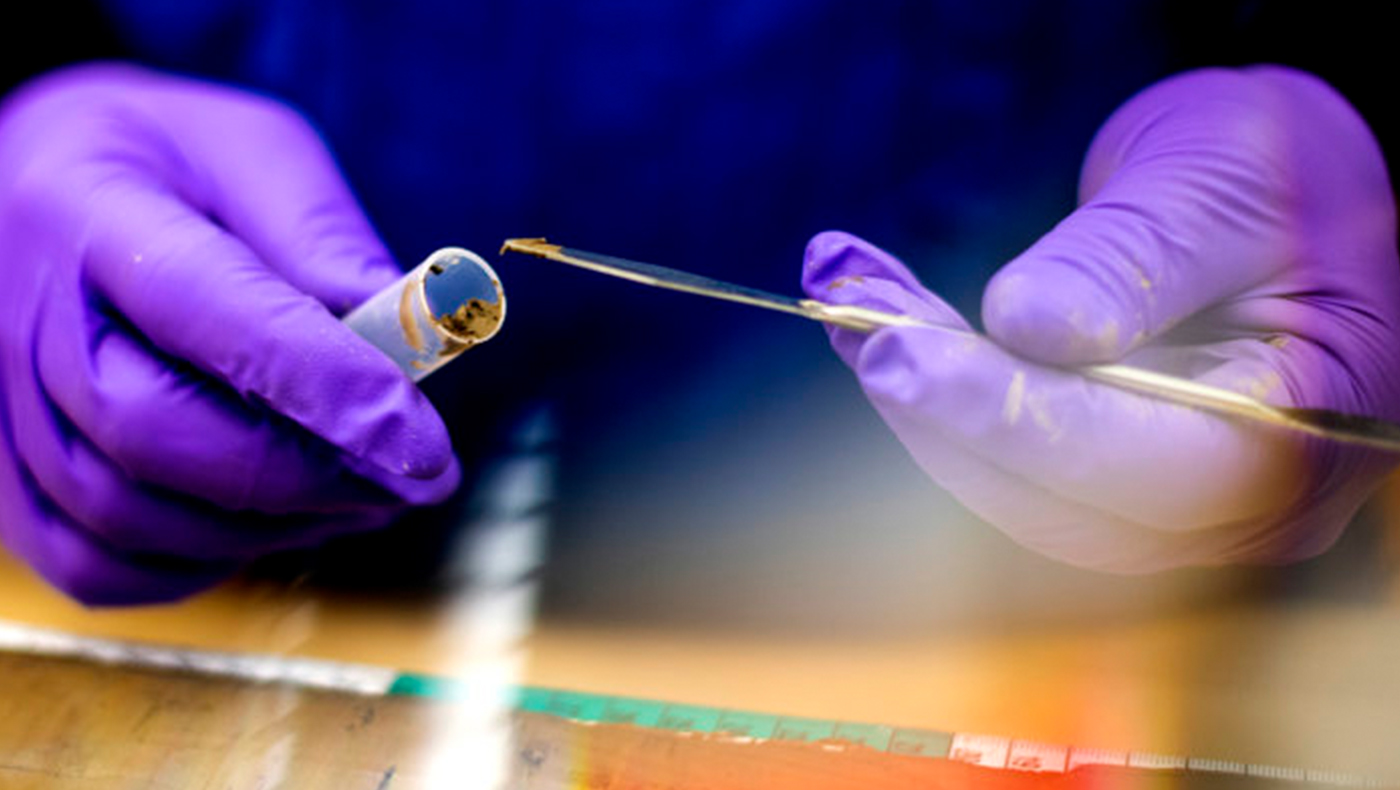

In long cylinders kept behind a large metal door in an underground bunker, Samuel Muñoz stores the keys to the past.

The tubes contain layers of sediment compacted over several thousand years on the bottom of lakes, bays, and other calm bodies of water. Some of them have traveled with Muñoz, an assistant professor of marine and environmental sciences at Northeastern, for the better part of a decade.

Using molecules left in the mud of an Illinois lakebed by long-dead bacteria, Muñoz and his colleagues have reconstructed ancient climate conditions in the midwestern United States. Their results, published earlier this year, could help us understand what’s in store for the region’s future as the planet continues to warm.

“Understanding climate extremes, like floods and droughts, in the midwestern U.S. has important economic consequences,” Muñoz says. “We need to understand what we’re in for, and be able to confidently project how the likelihood of extreme events will change going forward.”

According to reconstructions of our past climate, there was a period of unusual warmth and dryness in North America about 1,000 years ago. Researchers have previously used tree rings to determine that this period, known as the medieval warm period or the medieval climate anomaly, was marked by severe droughts in the Midwest.

But drought can be caused by multiple factors, Muñoz says. His team used newer techniques that allowed them to reconstruct the temperature more directly.

The researchers looked at organic molecules produced by microorganisms that are ubiquitous in soils and sensitive to temperature. When their living conditions get warmer or cooler, these microorganisms create more of one molecule type or another. By examining the mix of these molecules left behind in the mud, Muñoz and his team were able to infer past temperatures within about two degrees Celsius.

“This is the first time we’ve reconstructed temperature in this region,” Muñoz says. “And it shows that it was quite warm.”

Read more on Northeastern Global News.

Author: Laura Castañón